FADE IN

INT. PEARCE LIVING ROOM – DAY

JACK, 17, a curious yet quiet boy with brown hair and striking blue eyes, slowly wakes up on the couch in a warm suburban living room. Confused,

there are no photos anywhere. Empty hooks cling to the wall.

Jack attempts to sit up but has a strangely difficult time doing so. He looks and for the first time notices that his LEFT ARM IS MISSING. He begins to scream.

JACK

Wha… wha… My arm!

LEONARD

Jack. JACK. Listen to me there was a fire…

With his one arm, Jack pushes Leonard away as MACKENZIE PEARCE, 44, a strong-willed mother, enters and looks on with concern.

JACK

Who… who are you?!

LEONARD

We’re your parents. Dad and Mom. Jack, I know this is scary but the doctors said you would have some memory loss. You’ve got to trust me. There was a fire, and you lost your arm.

Jack slowly starts to settle into an exhausted, tearful state.

LEONARD (CONT’D)

We’re gonna fix it, though. I promise. Just lay down and get some rest. We need to get into your testing as soon as possible, but I promise that in no time I will make sure it is just like it used to be.

Jack sniffles.

LEONARD

Can you do that for me, bud?

JACK

Yeah.

LEONARD

(awkwardly)

Good boy. I lo… I’m really proud of you.

Jack lies down to rest, and Mackenzie and Leonard exit. Jack notices a blanket and rises to grab it.

Jack passes a COFFEE TABLE that is at the height of his thigh.

Jack lies down and drifts away to sleep.

EXT. PEARCE BACKYARD – DAY

Jack, Leonard, and Mackenzie stand in the middle of a pristine lawn. Leonard holds a full duffel bag and a basketball. He hands the ball to Jack.

LEONARD

Show us what you’ve got.

Jack dribbles the ball.

LEONARD (CONT’D)

(emotionless)

Good. What’s the capital of Washington?

JACK

What?

LEONARD

The capital of Washington.

JACK

Um… I don’t know.

LEONARD

(Irritated)

Take a guess.

JACK

Seattle?

LEONARD

No. Olympia. Can you use this?

Leonard pulls out a yo-yo. Jack shakes his head.

LEONARD

(growing in anger)

Are you sure?

JACK

I’ve never used a yo-yo. At Waterside we had one but it was broken.

LEONARD

Yes you have. And you went to Highland not Waterside.

JACK

Highland?

LEONARD

(ignoring Jack’s confusion)

How many cups of flour go in grandma’s pumpkin bread recipe?

JACK

(scared)

What?

LEONARD

How many cups!?

MACKENZIE

Leonard! Why does it matter if he knows? We can teach him all that.

LEONARD

BECAUSE CHRIS KNOWS! AUGH! JACK!

JACK

Dad?

Leonard gathers his composure and takes out a BAG OF CHOCOLATE and a BAG OF FRUITY CANDY.

LEONARD

Here. I’m sorry. You can have whichever one you want. But only one.

Jack chooses the chocolate.

Leonard sighs.

LEONARD

We’ll fix that later I guess.

Leonard storms into the house, leaving a confused Jack and a solemn Mackenzie.

INT. JACK’S BEDROOM – NIGHT

Jack, unable to sleep due to an ELECTRIC HUMMING noise, gets up to investigate.

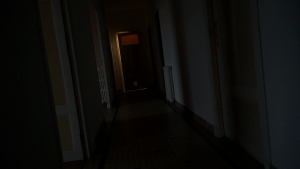

INT. PEARCE DOWNSTAIRS HALLWAY – NIGHT

The noise grows louder as Jack tiptoes towards a heavy wooden door. Hesitantly, he tries to open it.

The door is locked.

EXT. PEARCE BACKYARD – DAY

Jack sneaks around the outside of the house as he follows the noise.

Holding his ear up against a low, loose basement window, Jack confirms the noise is coming from the basement.

Grabbing some TONGS from a nearby barbecue, JACK pries open the window and enters

INT. PEARCE BASEMENT – NIGHT

Jack switches on a light and illuminates a dreary room containing an open cardboard box, a shelf containing boxes and picture frames, a set of stairs leading to a door, another door, and a capsule surrounded by wires.

Jack inspects the frames and boxes which are full of family photos. Jack is not in any of them. Instead, they feature Leonard, Mackenzie, and a YOUNG BOY. The boy appears to be Jack’s age and has the same brown hair and blue eyes, but a BIRTHMARK on his right arm makes it clear it is not Jack.

Jack climbs the stairs to the first door and opens it to reveal the downstairs hallway of the house. He quietly shuts it before heading to the second door. It is locked.

Finally, Jack approaches the capsule and hesitantly opens it…

Inside lies the body of a young boy in a pool of gel. There is a birthmark on a lightly burned right arm. Stitches line the top of the left arm, and the head is burned beyond recognition.

Jack, horrified, opens his mouth to scream, but is interrupted by Leonard and Mackenzie, dressed in pajamas, entering the basement.

LEONARD

(restraining fury)

What are you doing down here?!

JACK

Who is that? And who is that in the photos?

Leonard hesitates, but Mackenzie, oddly calculated and not missing a beat, responds.

What are you talking about? Those photos are of you. And I’m sorry you had to see the body, but that is simply the only way we could grow your new arm. Leonard has worked very hard for this and you won’t dare mess it up. Off to bed. NOW.

Fearing both the body and his parents, Jack scurries out of the basement and into the hallway, shutting the door behind him. Two steps into the hallway, he VOMITS.

With paper towels from the kitchen, he cleans the mess. As he cleans, he overhears Leonard and Mackenzie.

MACKENZIE (O.S.)

I don’t care if he isn’t perfect. Just do it tonight. It’s too risky to wait any longer. He’s too recognizable.

LEONARD (O.S.)

Fine.

Nervously, Jack finishes cleaning and scurries upstairs.

INT. JACK’S ROOM – NIGHT

Jack lies awake in bed and freezes with fear as the door slowly opens. Silhouetted in the light from the hallway is Leonard holding a syringe.

CUT TO BLACK.

In darkness, the NOISES OF AN ELECTRIC SAW are heard.

INT. PEARCE LIVING ROOM – DAY

“Jack,” in a long-sleeved, high-necked shirt, bolts awake, sweating. For a moment, he sits confused.

Then, he gets up and runs out of the room. As he does so, he passes the coffee table, which is strangely now at knee height.

INT. PEARCE BATHROOM – DAY

“Jack” enters, turns on the cold water, and splashes his face.

Noticing that the sleeves and neck of his shirt are getting soaked, he takes off his shirt to continue splashing his face.

However, when he does so, he notices that his right arm is slightly burned and contains a birthmark. The same birthmark as the body from the basement.

Looking up to the mirror in terror, “Jack” finds stitches lining the top of his left arm and the base of his neck.

LEONARD (O.S.)

Oh, good morning, Chris.

MACKENZIE (O.S.)

We weren’t expecting you to be up yet.

Horror seizes “Jack”/Chris’s eyes.

As the closing theme plays, the camera zooms out of the house to the street to reveal a street sign on a post: “ARDENNE ST.”

Attached to the post is a “Missing” poster depicting Jack.

FADE TO BLACK

Works Cited

Harari, Yuval N. Sapiens: A Brief History of Mankind. Vintage Books, 2015.

Hetland, Timothy John. “A Technology of Violence: Materiality, Discourse, and Victim Functionality in the Contemporary Horror Genre.” Dissertation Abstracts International, vol. 78, no. 1, July 2017.

Murphy, Mekado. “2017: The Biggest Year in Horror History.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 26 Oct. 2017.

Nerlich, Brigitte, David D. Clarke, and Robert Dingwall. “Fictions, Fantasies, and Fears: The Literary Foundations of the Cloning Debate.” Journal of Literary Semantics 30.1 (2001): n. pag. Web.

Petrov, Julia, and Gudrun D. Whitehead. Fashioning Horror: Dressing to Kill on Screen and in Literature. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Randel, Fred V. “The Political Geography of Horror in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.” ELH, vol. 70 no. 2, 2003, pp. 465-491. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/elh.2003.0021

Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft. Frankenstein: The 1818 Text, Contexts, Criticism. Ed. J. Paul Hunter. 2nd ed. N.p.: W.W. Norton, 2012. Print.

Smith, Angela M. Hideous Progeny: Disability, Eugenics, and Classic Horror Cinema. Columbia University Press, 2011.

Twitchell, James B. “Frankenstein and the Anatomy of Horror.” The Georgia Review, vol. 37, no. 1, 1983.

Top image: Creepy Bedroom

(Eumolp)